From Ann Lauterbach’s “Introduction” to The Night Sky:

…I have a desire for a practical aesthetics, wherein connections to the making or appreciation of forms have direct application to daily life, and daily life in turn inflects and conditions how to relate to the forms, artistic and otherwise, of the world. This shifting reciprocity is central to these writings. (4, italics hers)

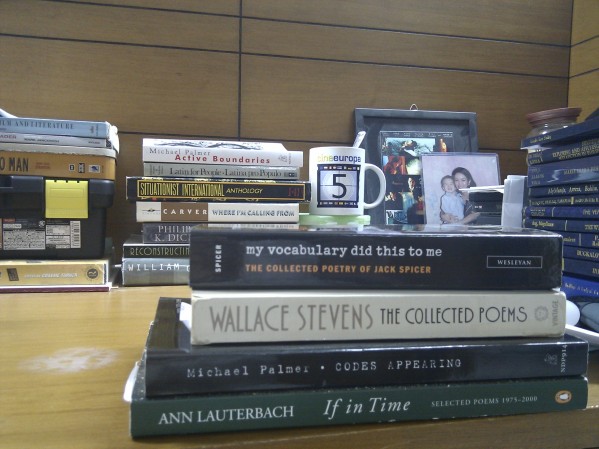

I’ve read those words several times before, and based on what else I’ve been reading deeply these days, Lauterbach’s words resonate with, say, those of Michael Palmer from “Octavio Paz: Circulations Of The Song”:

The first stirrings of vanguardism…can be found in the theoretical matrices of German and English romantic theory, with its revolution of forms, its conflating of genres, its collapsing of life into art and art into life.” (108-108, italics mine)

I also think of Wallace Stevens and the constant not-as-simple-as-it-seems dynamic of reality and imagination animating much of his work, and how it seems on one level to fit within the art-life scheme but, and I think this is important, not on others.

And then I think of Jack Spicer.

During the Vancouver lectures Spicer delivered shortly before he died, the poet was asked how Stevens fits into the notion of the serial poem Spicer discussed in detail in the second lecture. You can hear the question and answer on the audio clip embedded on this page, but here’s the quick answer: Spicer doesn’t really think “Notes Toward A Supreme Fiction” or “The Man With The Blue Guitar” conform to his ideal for the serial poem.

Spicer sounds a little unsure though, at least enough to somewhat concede a little and cite Transport to Summer (incidentally, the collection where “Notes Toward A Supreme Fiction” is found as the final poem) as coming close to what Stevens was trying to do in Harmonium. He’s unsure enough to say “I don’t know” before discussing instead what one may call the academic context of reception of Stevens (more on this later) and admitting that the term “serial poem” isn’t really very strong.

The first interesting point here is the emphasis on the book as the serial poem itself, which seems to me a play of scale (book = serial poem) similar to that found in a Symbolist like, say, Stephane Mallarme, whose “Crisis Of Verse” (PDF) ends with the following paragraph equating word with poem:

It’s an idea compelling enough to have been echoed in Hart Crane‘s “General Aims And Theories”:

(I’ve left out the part of “General Aims And Theories” that led to this sentence, but it’s worth reading for the explicit link Crane makes between the Romantic and the Symbolist when he mentions Blake and discusses matters in terms of innocence and experience.

The latter word, by the way, bears a rich set of etymological associations, one taken up by Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, from which that footnote was taken, and by Lauterbach, who not only writes within what she calls a “poetics of experience” but also links that word with the experimental.)

Nowadays, Spicer’s book as serial poem idea no longer seems so radical if, instead of grounding it in the dictation from a Martian radio–a science fiction update of traditional occult sources of the poetic as may be found in, say, Williams Yeats and Blake–we instead think of it in pragmatic terms. “The book as project,” for example, or what Natasha Sajé calls dynamic design and the structure of books. Also, the requirements of an MA thesis in creative writing.

So despite Spicer having it out with the Romantic tradition, when he offers the figure of the poet not as

a beautiful machine which manufactured the current for itself, did everything for itself—almost a perpetual motion machine of emotion until the poet’s heart broke or it was burned on the beach like Shelley’s—instead there was something from the Outside coming in

there seems to be a more complicated relationship going on between Spicer and Romanticism. (As an aside: I’m amused and shocked that Spicer would use as an example Shelley, who for Michael Palmer

represents a radical alterity, an alternative to the habitual discourses of power and mystification by which we are daily surrounded and with which we are bombarded. He represents a poetry of critique and renewal, rather than of passive re-presentation, a poetry which risks speaking to the central human and social occasions of its time, yet speaks from a decentered and largely invisible place. It exploits the margins to speak as it will, out of difference, rather than as it is always importuned and rewarded, out of sameness. (204)

But there’s something else going on here, and it has to do with the academic discourse framing Stevens in 1965. Right after Spicer tries to half-heartedly discuss the aesthetics of Stevens’s work by means of the serial-poem question, he says the following oft–quoted remark, expressing with more conviction why he “distrusts” Stevens:

The awful thing I’ve noticed about Stevens that I’ve noticed is that everybody in English departments who hate poetry, which is just about everybody, loves Stevens. I liked Stevens a great deal more before I saw that. You get somebody you know very well just hates poetry, like some people hate baseball or French movies like I do. You know there’s just a real weird hatred. Well, they always like Stevens, all of these people. And the more they hate poetry as it is in the process, the more they like Stevens. So although Stevens moves me, I’ve gotten more and more distrustful of him.

As strange as it may be to connect Spicer and Louise Gluck, I can’t help but remember how she also feels a similar distance towards Stevens, assuming of course that distrust can be rightly considered distance and a lack of intimacy and nearness. I think it does, somewhat, and that’s where an interesting dynamic of agon takes place.

I found Aliki Barnstone’s essay on Hart Crane moving precisely because she struggles against Crane and herself: “My intent when I began this piece was to defend Crane, but as I reread, I found myself recoiling. I’d never written about a writer I wasn’t in love with, and now I’d fallen out of love with Hart, viscerally.”

Similarly, I like it when a struggle with Stevens takes place in poems by, say, John Berryman, Terrance Hayes, Cole Swensen, or Frank Bidart. (I guess, for the sake of consistency, I should also say that I like my bitter struggle with what seems to be a Bloomian preoccupation, despite some misgivings I may have about some of his critical judgments.)

And so, I go back to beginning, though I’ve digressed so much that I’ll have to talk about this in another entry.

That bit from Lauterbach at the very top? The “practical aesthetics” she italicized and which she links to her “poetics of experience”? That rang a bell with me when I read it recently, because just before I did, I read an early Jack Spicer poem where he struggles with Stevens from an aesthetic, rather than discursive, perspective. It’s an apostrophe to “Mr. Stevens” and the repetition of that address at several points in the poem sound to me like a snotty punk kid doing an “Officer Krupke” spiel.

The title of Spicer’s poem? “A Lecture On Practical Aesthetics.” Emphasis frigging mine. But I’ll write about this next time. This has gone on too long.