Peter Gizzi‘s name mentioned in a meeting I had with my thesis adviser (hi, sir!): did it really happen, or did I just imagine it?

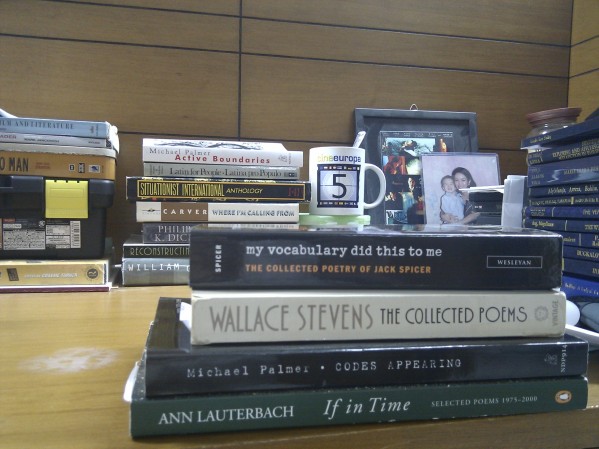

Can’t verify with a brain still fried from grading final requirements, but if my adviser did mention Gizzi, asking me if I knew the poet, I’m pretty sure I would have said, “Yes, I’ve read some of Gizzi’s poems here and there, but I mostly know him for having co-edited the collected Jack Spicer.”

Kevin Killian, the other editor of My Vocabulary Did This To Me, seems, to me, a “louder” and more outrageous figure. He’s long had my attention with two collections of poetry, one of which is centered on Kylie Minogue and the other on Dario Argento.

Still, Peter Gizzi seems to have been humming in the background all this time. Humming like a current of electricity, humming like an undercurrent of song. To whit:

“Poetry At The Threshold: Peter Gizzi Interviewed By Ben Lerner”:

Singing is a perilous business. What does it mean to be next to oneself, seeing and/or singing one’s self in time as a rhetorical figure, disembodied and refigured as an embodied line of verse? To be spoken not just in the act of writing, but to be spoken and present and remain intimately embodied in some posthumous time as well—to accept this haunted occupation of poetry?

Publisher’s copy: “The poems in Threshold Songs tune us to the microtonal music of speaking and being spoken.” [emphasis mine]

Aside from some great comments about punk (” I can hear Dickinson’s spiky, haunted, rebellious, and eerie tunes as punk” and “What’s “punk” in all this is the DIY reality of the homemade, the raw voice, with its asymmetries, its reaching, and its limits,” to cite just two) , the BOMBLOG interview with Gizzi also has him say

I think of poetry always as a territory and imagine sound as a sculptural element, in the sense of being held in an abstract or aural environment, as when one is listening to a piece of music. So it’s the same with the music of the poem, whether it be a kind of inspired talk or a richly coded lyrical run. It’s a sound, after all, and so you can return to your place in the world, or better yet, discover your place in the world, within the music of the poem, and that only happens in the act of listening. It’s dynamic. It clears a path for me to go deeper into my own interiority and to light every corridor and chamber and discover what’s there.

From the older jubilat interview with Gizzi:

- “I like the word bewilderment because it has both be and wild in it, and I can imagine also wilderness inside it as well.”

- “Again, I’m not only interested in a history of the lyric but in a more ontologically complex reality of lyric history.”

And still further back to 1998, Burning Deck’s publication of Gizzi’s Artificial Heart is accompanied by the following remarks, which seem to me a good description of what I’m trying to do in my own work:

Formally the collection is a sampling of lyric history from the troubadours to post- industrial punk: it sustains the haunting quality of a song heard from a distance, overlayed with playground noise, lovers’ oaths and cries of loss.

From the Rain Taxi review of Artificial Heart:

One telltale aspect of Gizzi’s heart is his love of music. This shines, surely, in the content of the poems: “New Picnic Time” is named for a Pere Ubu album, and “Fear of Music” after one by Talking Heads; both poems “sample” the lyrics of these band’s songwriters in seamless and engaging ways, turning their punk postmodernism to his more archly crafted ends. But more importantly, Gizzi’s impeccable sense of line and of stanza create a fine and delicate music throughout.

…

Gizzi’s gorgeous musicality marries his abstractly conjured imagery in a wedding of non-linear bliss, once again demonstrating that the heart of poetry, artificial though it may be, veers away from sense and always toward beauty.

Marjorie Perloff’s review of Artificial Heart has her talking about “a tantalizing new lyric mode” in Gizzi’s post-Language poetics (is she really talking about the Third Way?!) and also has her invoking Hart Crane (who tends to critically “belong” to Harold Bloom) and saying:

…the notion throughout Artificial Heart that the lyric poet is once again writing trobar clus–the allusive, oblique, hermetic lyric of the troubadours–a poetry of secrecy.

Also: Perloff’s introduction to Young American Poets, also from 1998, has her talking about Gizzi and several other poets, including Cole Swensen, in the context of “an exciting moment for lyric poetry.”