And now, Cole Swensen, with five poems from the same journal where I read Stuart Dybek. Although I’ve listened to a lot of the clips on Swensen’s Pennsound page, I’ve never quite had the chance to actually go deep into Swensen’s work, apart from some rather tangential encounters:

- the list of poems Swensen recommends as “required reading” has me vigorously nodding along in agreement

- a teacher mentioned her in passing a few years ago, and my ear caught on Swensen’s first name, which is the same as my son’s

- Nick Lantz‘s ruminations on Swensen’s Goest were beautiful and insightful but now sadly taken down from his blog archives*

- two years ago, I bought Caroline Dubois’s You Are The Business, which Swensen translated from French

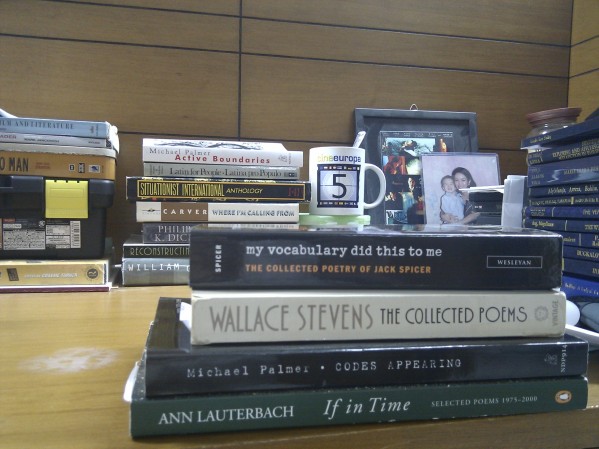

Now I don’t think I can write about Swensen as well as, say, Forrest Gander does here, but I can gush over, say, how the first two poems combine prose sections with the usual lineated stanzas. It’s a “look” (shape? structure? form?) I’ve always loved in the works of Jack Spicer, Michael Palmer, and Ann Lauterbach, though I’m ashamed to admit I don’t know of any earlier instances. (George Oppen and Louis Zukofsky maybe? Egads, I need to bone up on my history.)

In terms of title and content, I should like “What Is On The Page” a lot and I do, actually. Swensen’s poem begins with “There is no ink on the page but a shadow,” and ends with “…I do not allude, though / we are fond of words / and use them when we can.” I’m reminded of some of Michael Palmer’s 80s poems though, as well as my own proclivities. I can read “What Is On The Page” again and again like a close friend, but it doesn’t quite make me feel as if the top of my head had been taken off. It’s comforting, which is both good and bad.

That the second of Swenson’s poems here is called “Bastille Day” is appropriate. My head does feel taken off, blown off, with lines like: “I finish the letter as the sky fills with toy windows, the smell of water and an irregular pulse.” I’m not sure what it means, but these images are provocative, stronger in their effect on me than the metalinguistic pronouncements of “What Is On The Page” (although it does have the beautifully enigmatic “…the ocean / left out in the rain you wear for dying”).

The three poems that follow are more formally conventional: no hybrid of prose and lineated verse, just the latter in the irregular short lines common in the contemporary lyric form. But I just love these, because they certainly belong to Visiting Wallace and should have been included in that anthology: “Wallace Stevens Waking At Night,” “Wallace Stevens Walks By The Sea,” and “Wallace Stevens Walks Along The Beach At Night.”

Interesting linkages going on here, as evinced from the titles and some recurring words and images. The first poem begins with “Something from the dark sea / rises and flies,” and it becomes an easy temptation to read the other two poems as happening in the same “imaginative space,” especially when the second poem starts with “And now it is that it rises” and the third with “The edge of the dark sea rose.”

(Some questions: why is the first poem in the third-person–a “he” which seems to be Stevens–but the other two use the first-person?)

Some of the words and ideas also appear freighted with significance in Stevens’s own poems: the sea and the ocean, flight, “…what freedom / resists the mind and everything” from the first poem. The second poem repeats some of these and adds “Everything beautiful is also in motion,” motion and movement being important to Stevens since Harmonium and after.

Things get really interesting for me though, in the third poem. There is “a ghost in an open mind,” but this phantom becomes flesh by an insistence on the carnal and the emotional not always seen directly in Stevens: “And that which might have been a man / made of blood and love and grief.” There is a necessary violence before we reach the late-Stevens sense of simplicity (the plain sense of things, perhaps?) and slowness, and the direct rhymes emphasize the words: “The world rocks down to its / direst simplicity / and the shock of evening / which settles in slow.”

And when it ends with “Far back in the town / I hear my house burning,” this image of a noisily-burning house, one that is heard as it burns, is a shock, certainly unlike the quiet decline and abandonment of “[t]he great structure [that] has become a minor house.” The destruction is closer to the aural Sensurround-Stevens of Harmonium, rather than the quiet physicality of a late poem like “The Rock.”

I don’t know whether Swensen has other poems directly addressing Stevens like in these three poems. I don’t think she needs any more–these three have more than enough substance to work with–but if she has more, I for one would love to read them, as atypical it may be of her usual work.

Bonus: a blog entry on Swensen’s identification of “four specific modes of ambiguity.” Now I’m interested in Noise That Stays Noise, her book of essays.

* If I remember right, and I may not, Lantz had a three-part reflection on the ghostly in three poetry collections. Though I can no longer be certain, I have a lingering impression that one of the two other pieces was on Cornelius Eady. I wish I saved a copy of those pieces. Aside from Lantz’s poems, those pieces were instrumental in getting me interested in him as a writer.